Hybrid drives: Siemens sends in the machines

Encouraged by the success of a hybrid drives program, Siemens is going all out in Norway to automate production of that core marine energy storage enabler, the lithium battery. Offshore service vessel charterers, rig owners, ferry operators and ship owners are the target market. Trondheim’s technical university and a recent history of hosting battery makers and system integrators has made it launchpad for new applications involving the new BlueDrive Plus C drives and batteries.

Siemens’ Norwegian head of strategy and business development, Odd Moen, is full of insights: “You know that one kilogram of cod costs a trawler 0.5 liters of marine fuel oil to fish,” he says, his serious expression becoming milder. “You really ought to put a bottle of (motor) oil on the table with your bottle of wine.” In fact, cod’s carbon footprint is said to be 356 grams of CO2 for every 0.256 of fish, a nod to fishing hard on marine fuel.

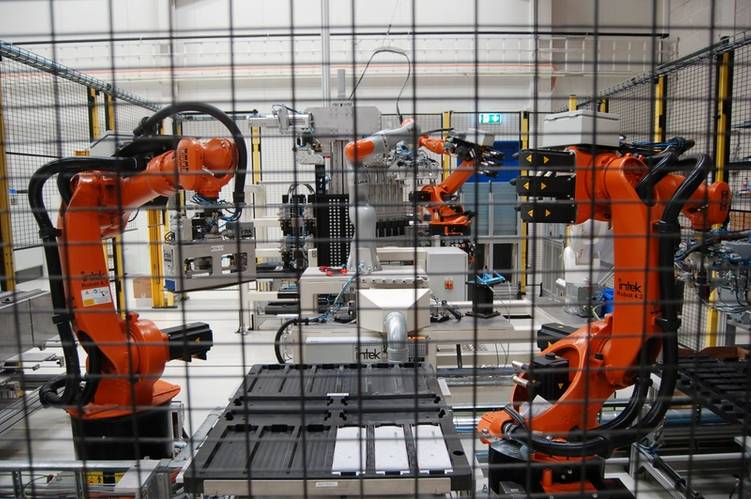

His point made, Moen walks us into Siemen’s brand-new factory for making marine energy storage systems, or ESS, the heart of a plan to equip and sell more BlueDrive Plus C drives. The new drive is said to be a safer, more profitable and a greener option for shipowners of all but the largest vessels. The factory is just a few weeks old but expects to serve “oil, gas and other future-oriented vessels”. A year ago, the plant agglomerated batteries by hand (not the first to start that way). Now, robots do the mundane work of building stacks of battery packs from behind metal fencing. Several of these tireless, orange-armed workers stack and swivel at a steady clip.

“We expect the market will double in three years,” Moen tells Maritime Technology Reporter as others admire the slick machines. He gives a cautious nod to taking photos. After all, the making of marine ESS in Trondheim has, behind the scenes, been a battlefield of sorts. Of two Canadian companies, Corvus and PBES, only Corvus survives. PBES retreated to find life producing from a new factory in Germany.

Integrated integrator

Siemens, as both system integrator and marine ESS maker, has an obvious advantage in no longer having to wait on fitful battery production. Call it an integrated integrator. Needing to be served in the immediate vicinity are Norway’s increasingly green fleets of all-battery and hybrid-power coastal ROPAX and offshore vessels. Increasingly, Moen says, there are orders for ferries and a growing list of larger vessel types. “A small number of batteries yields huge results. Eight cubic meters of battery packs are all you need for the huge new vessels.”

To produce these in a hurry, Siemens sent over this very troop of 12 articulated, dual-arm and palletizing robots. We were among the first visitors, and some robots were still covered in their factory wrap. Digitally controlled production — with barcoded quality control throughout the value chain — was what we were watching, as robots simulated bent, burdened backs and the tool-twists of a handful of technicians. Already, Moen’s bots can produce enough batteries for 300 to 400 ferries per year.

On the product, we note that waver-thin channels for battery coolant seem to indicate a Siemens quality production technique from the Continent. “Not China?” we ask. “No,” comes the answer. Moen, who has some of the air of a M.A.S.H surgeon, is at pains to explain the new-style Siemens battery’s water- and cell-temperature transfers, as well as the wireless monitoring and control of these systems. Why wireless? “It would be too huge a number of signal cables otherwise,” he says. One of these modules weighs 60 kilograms but can replace “tons” of gargantuan ship engine parts. Indeed, the BlueDrive Plus C drives also enable battery-only vessel power for ferry shorter-crossings.

A robot’s battle against emissions: Siemens articulated robots of different sizes assemble battery stacks at Trondheim, Norway.

A robot’s battle against emissions: Siemens articulated robots of different sizes assemble battery stacks at Trondheim, Norway.

Credit: William StoichevskiPrecursors

Integrating batteries into onboard power systems isn’t new for to Siemens. What’s new is the demand — dozens, possibly hundreds of ferries plus a range of small and mediums-sized vessels orders — and a pipeline of new concept vessels.

The company has been in Trondheim for 110 years, and half of its 600 employees are engineers (although many, invariably, would be of a specialized Norwegian engineer cohort of old that might be more technician than engineer). Nonetheless, Siemens employees plenty new M.Scs and Ph.Ds here, and nearby NTNU university is a hybrid-drive recruitment base. Outside, Moen points to a red-painted building where the company is developing electrical power for remote, subsea oilfield developments. Years of Siemens electrical switching development make it all possible, marine drives included.

In fact, Siemens first electrically propelled platform supply vessel appeared in Norway in 1998 after a ship-owner challenge that took three years to answer. Moen recalls that while it cut fuel use by 35 percent, getting it off the ground exposed supplier shortcomings: “How to speed up supply chain learning became a focus along the way, just as with the first LNG-powered ferry. We delivered it as well as the first (hybrid) long-liner fishing vessel.”

Better with batteries

Three years ago, Edda Freya — “the most environmentally friendly offshore construction vessel” — delivered 30 percent fuel savings, charterer Equinor says, despite having six diesel engines driving its propellers and charging its four battery packs.

Before that, it was the “world’s first ever electric fishing vessel”, one that allowed more space for a fisherman’s haul and, if used throughout the fleet, would use 180,000 t less fuel yearly while emitting 540,000 t less CO2 “after charging all night for about six euro”. That first vessel used an ESS with “the batteries of two Teslas” to cut fuel bills by 90 percent (assuming electricity prices of EUR 1.2 per kilowatt hour). “If you produced electricity in a (gas-fired power plant) you’d hardly (notice).”

As for biofuel — “We’re not against biofuel, but a fishing fleet purchase of firewood for fuel would have to fell 50 percent of all currently felled trees,” Moen says, adding, “Fishing vessels represent 17 percent of all marine fuel purchases (in Norway).

High-profile cruise

Meanwhile, Siemens as systems integrator got full marks for enabling the 2019 Ship of the Year winner, Color Hybrid, setting the tone for cruise vessels with its battery-propelled 5 MWh of mean power at 12 knots. The vessel also boasts 20 percent less green house gases.

This first incarnation of plug-in vessels showed Siemens BlueDrive Plus C diesel electric hybrid system could make a difference in an industry-wide quest for low-emissions vessels. Already, zero-emissions operating profiles will be required to cruise the Norwegian fjords; steam into a number of European ports or ply Emissions Free Areas.

When operating in those areas, Siemens redundant brain for “plug-in” hybrid vessels — the Siemens Mind Sphere Cloud system — offers a forecast of optimum charging times. Regions with limited power (and usually high electricity prices) at certain times make up part of an electricity forecast that includes the effects of weather forecasts on charging availability (as in conditions and supply).

BlueVault battery tech

For this integrated provider, the list of vessel types is growing. Rows of battery cabinets on a car ferry that’ll serve the west coast of Norway are nod to the power redundancy needed on exposed stretches of coastline.

As Siemens R&D is brought to bear, a 6-kWh power module is more evidence that batteries and drives are now available for different operational profiles. Vessel owners are being told they can have longer life batteries and shorter charge cycles.

“Batteries are about to become of increasing importance to the marine industry,” Moen says, with the “Why” open for interpretation: competition, constricted operating areas and maybe conscience. However, system life — even with battery prices falling “10 percent yearly” — needs to improve from the 80 percent of battery capacity that remains when “end-of-use” is declared. And with this, the “pollution argument” goes “out the window”, as a seasoned shipping industry observer puts it. Yet, the emissions argument is still a good one.

Hybrid benefits

It took years of research to learn that drives could control power to provide better fuel savings than both liquefied natural gas and duel-fuel engines. Duel-fuel and LNG plant also proved costlier to install.

The lower CAPEX and greenhouse gas emissions said to be derived by hybrid drives is coupled by an incremental increase in available power, as an adjustable combustion engine is made to provide timely power output. It’s a selling point for captains, although ship owners might be more familiar with the “less wear and tear” aspect of these drives. Both are cost arguments, but as with less noise, LNG offers these benefits in spades. Siemens hybrid tech, however, now has upwards of 40 customer references in far shorter order that what happened with the scale-up with LNG.

This newest raft of tech — the BlueVault batteries and BlueDrive Plus C — will need fewer batteries. “We’re still learning, but we’ve been pioneers in the use of batteries,” Moen says, a nod to Siemens battery integration efforts from Australia to Norway that have yielded at least 25 passenger ferry references, a major cornerstone of the battery-hybrid business. Five years on, the MF Ampere was first among a series of all-electric ferry newbuilds and retrofits paid for by a Norwegian government keen to take a green marine lead on the world.

There’s much at stake. A study reveals about half of all ferries in Norway (about 223) can be converted to electricity or hybrid. A slide Moen shows us suggests annual savings of 100,000 t of fuel and 300,000 t of CO2 can be derived if 127 ferries went all-electric and hybrid. “The politicians understood it,” Moen says, adding that the logic of battery power was clear.

Of course, as with hydrogen, there’s one glaring hole in the whole “let’s get on batteries now” argument, and that’s the prevailing “low grid capacity for charging”.

“All (local) dishwashers would go out,” Moen cautions, explaining that, “Traditionally, you’d upgrade the transmission lines, but putting batteries in huts on the dock would enable batteries to be charged from available energy then transferred to (a ferry). A smart grid uses the existing grid.”