When it Comes to Workboat Engines, the Future is Flexible

Vessel owners are making new fuel choices, but increasingly, they have options to help reduce the risk of doing so.

The latest engine developments aim to make it easier for owners to avoid the chicken-and-egg fuel price and availability risks of new fuels.

As Roger Holm, President of Wärtsilä Marine and Executive Vice President at Wärtsilä Corporation recently pointed out, the challenge is that owners won’t commit to a fuel today that is expensive, only produced in small quantities and may be usurped by another fuel that scales faster and more affordably. Meanwhile, it is difficult for suppliers to scale production without clear demand signals.

The problem is particularly pressing for vessels that are reliant on what fuels are available in particular ports, and some of the pioneering efforts are occurring in major bunkering hubs.

In May this year, JMS Sunshine, the world’s first LNG-powered tug (with two 16-cylinder MTU gas engines) entered operation in Singapore.

Singapore’s first LNG bunkering vessel, FueLNG Bellina, commenced operation in March 2021, and in December 2023, Singapore welcomed its first methanol bunkering vessel.

Also in May this year, the world’s first methanol-powered tug, Methatug, entered operation in the Port of Antwerp-Bruges (powered by 8-cylinder ABC engines).

Government funding and regional regulations are playing a part in generating change. The Norwegian government, for example, has announced that it will establish requirements for zero emissions from new supply vessels from 2029. Pioneers are active there. Wärtsilä recently signed a contract with Norwegian shipowner Eidesvik to supply the engine equipment for the conversion of a PSV to ammonia fuel. The Viking Energy, which is on contract to Equinor on the Norwegian Continental Shelf, is scheduled for conversion in early 2026.

The three companies have a history of collaboration and innovation. Using Wärtsilä dual-fuel engine technology, Eidesvik became the owner of the world’s first LNG-powered PSV back in 2003.

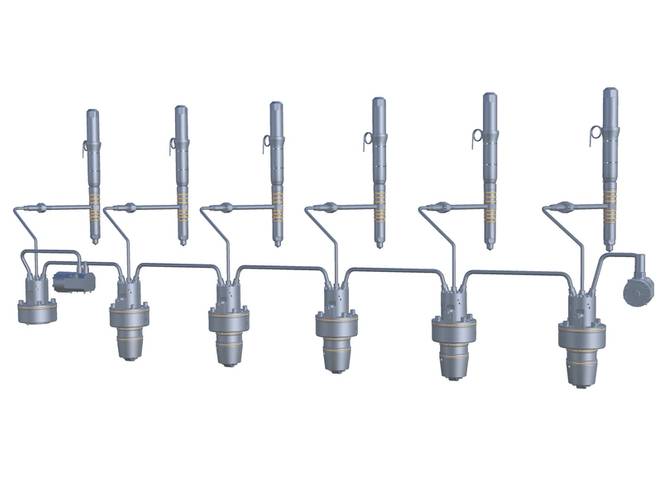

In September, ABC Engines launched its Evolve 8EL23 engine, completing its range of engines that can operate on a range of fuels.

In September, ABC Engines launched its Evolve 8EL23 engine, completing its range of engines that can operate on a range of fuels.

Source: ABC Engines

A 2024 report by Wärtsilä estimates that fuel efficiency measures can cut shipping emissions by up to 27%. However, sustainable fuels will be critical to eliminating the remaining 73%. Holm noted at the time that achieving net zero in shipping by 2050 will require decisive policy and industry collaboration, and the report states that the EU Emissions Trading Scheme and FuelEU Maritime Initiative will see the cost of using fossil fuels more than double by 2030. By 2035, Wärtsilä predicts these regulations will close the price gap between fossil fuels and sustainable fuels.However, even with price parity, availability risks remain, and OEMs are supporting owners on this front with fuel-flexible engines. “Investing in fuel flexibility is the most financially viable way to avoid the risk of stranded assets,” says Holm. Wärtsilä’s latest engine type, the Wärtsilä 25, is a medium-speed 4-stroke modular engine that promises easy upgrades to support future low or zero carbon fuels as they become available.

Other OEMs are offering solutions.

In September, ABC Engines launched its Evolve 8EL23 engine, completing its range of engines that can operate on different fuels thanks to a versatile cylinder head design which allows for straight-forward conversion between liquid, dual and gas fuels.

In June, Bergen Engines announced that its natural gas engine can burn a 25% hydrogen blend without modification. This builds on the successful commercialization of a 15% hydrogen blend option in 2022. The OEM aims to have a 100% hydrogen-fueled engine by the end of the year.

Despite the technology advances, new fuel availability is likely to be a concern for some time yet. A study released in June 2024 by Transport & Environment (T&E) states that 4% of European shipping could run on e-fuels by 2030, but just a third of the projects to supply the fuels are guaranteed, as fuel suppliers fear a lack of demand.

Biofuels such as HVO and FAME are an already-available option for an increasing number of engines. Bergen Engines announced in May that its B33:45 engine has received formal approval for operation on blends or 100% HVO.

However, NOx regulations mean that hydrocarbon engine OEMs are also focusing on aftertreatment advances.

MAN Engines has increased its range with a new D3872 V12 engine. The result is that in-line six-cylinder, V8 and V12 engines from 221 to 1,618kW (301 to 2,200 hp) with a displacement of 12.4 to 29.6 liters are currently available for light, medium and heavy-duty marine applications. The new 30-liter 2,200hp engine can be combined with a modular SCR to meet EPA Tier 4 or IMO Tier III standards and optionally a particulate filter to meet EU Stage V standards. The OEM says the SCR also reduces fuel consumption by 3-8%.

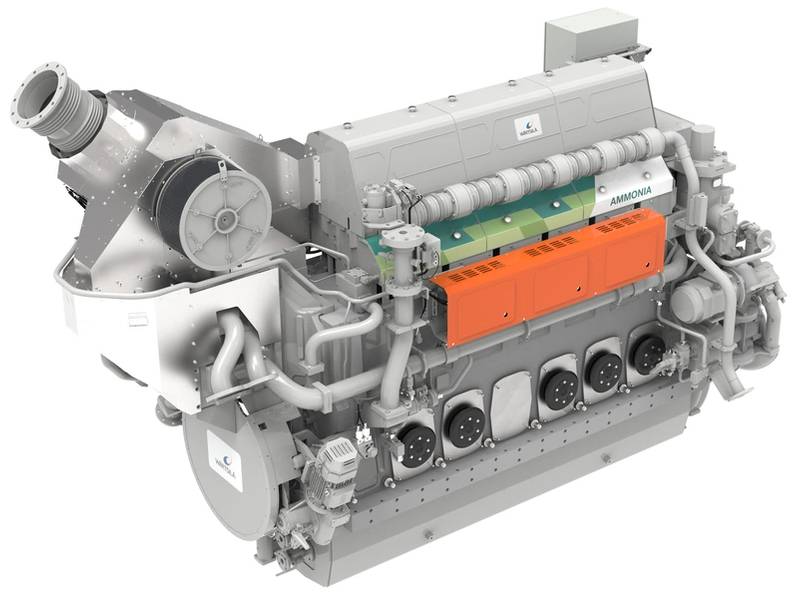

The Wärtsilä 25 medium-speed 4-stroke modular engine promises easy upgrades to support future low or zero carbon fuels.

The Wärtsilä 25 medium-speed 4-stroke modular engine promises easy upgrades to support future low or zero carbon fuels.

Source: Wärtsilä

Volvo Penta has expanded its range of D8 IMO III solutions aimed at smaller, high-speed commercial vessels. The new solutions feature six-cylinder, 7.7-liter diesel engines that can provide power up to 405kW and generate up to 550hp. The associated SCR technology has been optimized for heavy-duty operations and can be installed in either a vertical or horizontal position.In September, MAN Energy Solutions announced a new common rail injection system for its medium-speed, four-stroke portfolio which the OEM says optimizes engine performance, emissions and fuel consumption. CR 2.2 brings an increased system pressure of up to 2,200 bar to enable it to comply with future emission limits while offering the best possible fuel consumption. It also acts as a platform for a broad variety of fuels including HVO and FAME.

With all these developments, OEMs are providing the equipment to reduce fuel consumption, NOx and CO2 emissions. Adding modularity and fuel flexibility, they are facilitating change to new fuels.

The Wärtsilä report indicates that every dollar an operator saves in fuel costs at today's prices could be worth 3-5 times that by 2030. So, says Holm: “Taking steps to improve fuel efficiency and invest in fuel flexibility can deliver immediate returns, reducing both emissions and operating costs. But action must be swift – we have the lifecycle of just a single vessel to get this right.”

In May this year, JMS Sunshine, the world’s first LNG-powered tug (with two 16-cylinder mtu gas engines) entered operation in Singapore.

In May this year, JMS Sunshine, the world’s first LNG-powered tug (with two 16-cylinder mtu gas engines) entered operation in Singapore.

Source: MTU